As the 2023 Brics summit kicks off SA is perfectly positioned as host to wield considerable influence. Several significant issues are in the media spotlight, including the UN sustainable development goals, the climate crisis and every country’s imperative to embrace a “just transition” while ensuring economic growth, and the soon-to-expand membership of Brics itself.

What is not in the Brics spotlight is the need for countries to address, together, urgent matters of public health — specifically obesity-driven noncommunicable diseases — that disproportionately affect low- and middle-income countries and cost Brics (and others) millions of lives and billions of dollars every year.

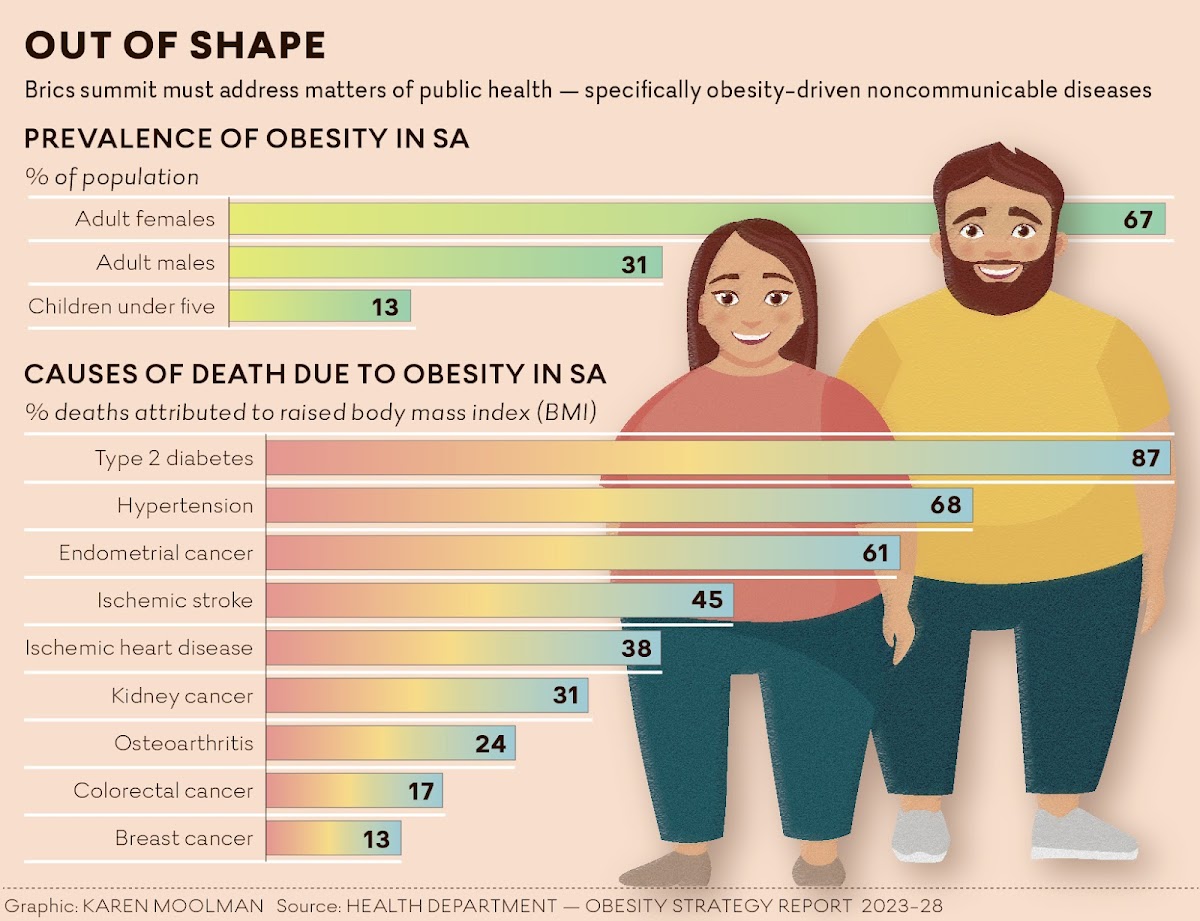

The Brics countries together represent 40% of the world’s population. In these five nations and across the globe there is a significant and mounting burden of obesity-related illness such as diabetes, high blood pressure and cancer at ever-younger ages. The consumption of sugary drinks and processed foods high in sugar, salt and saturated fats is fuelling these pandemics: noncommunicable diseases are now the number one cause of death and disability worldwide. (In SA, diabetes alone affects 12% of the adult population and is doubling every decade. It is costing the fiscus R33bn a year — and that’s just for the 40% of people who are diagnosed and treated.)

All of this is happening simultaneously with health reforms for universal health coverage, especially in India, Brazil and SA. At the same time, while Brics countries have some single-issue policies for food (taxes on sweetened drinks in India and SA, for instance, and mandatory sodium targets in Brazil and SA), overall they lack adequate policy to safeguard the public (and the fiscus) from the fatal effects of diet-influenced diseases.

The causes are many, not least poverty and structural racism. But economic policies, development agendas and social norms support harmful “commercial determinants of health”. Translation: private sector activities that affect people’s health, directly or indirectly. At the heart are multinational agri-processing companies that control and shape food systems that actually cause and promote ill health through cheap, highly profitable ultraprocessed products. Evidence increasingly shows that these are costing us our lives and accelerating climate change.

These companies’ activities are primary examples of “commercial determinants of health”: food and beverage companies have explicit strategies that harm health, including relentless marketing of foods high in fat, sugar, salt and additives, starting in infancy and continuing to target children in particular, who are most susceptible to marketing influence.

Because sales of cheap ultraprocessed foods and sugary beverages are reaching saturation in high-income settings, the focus of the multinational agri-food industry has shifted to emerging markets, including the Brics nations. In some of these and other developing countries the relative lack of laws and regulations prohibiting these strategies, or the inability to enforce those that do exist, enables industry to quickly penetrate these markets and sell their highly profitable, dangerous foodstuffs. The entire Africa is considered a growth market by most multinationals, enabled by weak regulation and cheap advertising that promotes unhealthy aspirations.

The burden of disease in SA, especially among women, is now led by diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The only way we can tackle it is by managing how our societies deal with what is in effect a new form of colonisation — by “Big Food”. Take the case of SA’s sugar tax, introduced in 2018 and recently proven to have curbed the sale of sugary beverages among low-income groups that are particularly badly affected by obesity, diabetes and other related diseases.

Recent research shows that people are responsive to the sugar tax: sales of sugary beverages in those groups have dropped. It allows people who are the most vulnerable to be responsive. The World Health Organisation recommends a higher level of taxation: 20% rather than the initial, and current, 11%. But the Treasury has avoided increasing the sugary beverages tax even by inflation for the past five years — it is now about 8% in real terms — because of approaches by the SA Cane Growers’ Association lamenting the loss of jobs in the sugar industry (which has been ailing for other reasons, in any case).

While Brics governments have shown commitment to tackling noncommunicable diseases through specific national strategic plans, they are not yet committed to tackling the “commercial determinants” of their noncommunicable disease pandemics. There is an opportunity for the Brics’ health, trade and finance ministries to collaborate on establishing innovative models and platforms to address obesity-related diseases, and at the same time to legislate and regulate the activities of multinational food and beverage companies. This must include regulation of pervasive and relentless marketing by food and beverage companies, especially to children, which is central to the multinationals’ growth strategies.

There is no single silver bullet. Prevention and health promotion are critical, and countries need to adopt a synergistic suite of policies to make sure they work. Chile, though not (yet) a Brics country, has led the way since 2016 with a perfectly comprehensive suite of policies that reaches far beyond the “single-issue” food policies many countries have introduced, such as sugary-drink taxes or front-of-pack labelling of foods.

Chile’s food labelling & advertising law takes a three-pronged approach: it mandates black-and-white warning labels on products high in calories and “nutrients of concern” (sugar, salt or saturated fat); it bans all advertising of those products on “child-focused” television, digital media and cinemas; and food and beverage companies are banned from using child-directed advertising. In 2021, The Lancet reported a sharp decline in Chileans’ purchases of those foods.

What needs to happen now is for SA (which has promising food labelling legislation soon to be approved) and the rest of Brics to lead developing countries with stepped-up, similarly comprehensive policies, to help shift food systems’ commercial “growth” imperatives and practices to human and planetary health and development imperatives. The cost of inaction is already too high.